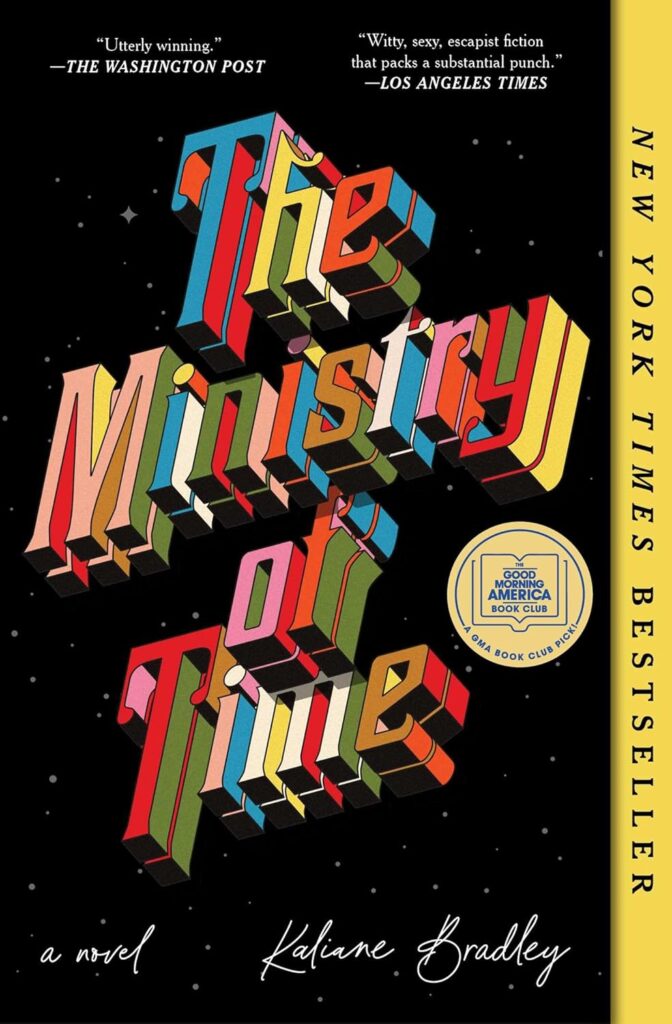

What if the British government discovered time travel and decided the best use of this world-altering technology was… bureaucracy? That’s the delightfully absurd premise of Kaliane Bradley’s debut novel, which asks what happens when you pluck people from their doomed historical timelines and drop them into modern-day London.

In the near future, the UK discovers time travel and forms the Ministry of Time. The Ministry’s first actions are to test the time travel machine by bringing historical figures back to the present—temporal rather than geographical refugees known as expats in Bradley’s book. Each of the expats is paired with a partner known as a bridge to babysit them in their new reality while the ministry observes and tests the viability of time travel.

Our protagonist is one such bridge—the daughter of a Cambodian refugee mother and English father—paired with Commander Graham Gore, a First Lieutenant from Sir John Franklin’s doomed 1845 Arctic expedition. Gore, who was destined to perish somewhere on King William Island alongside all 129 crew members, now finds himself navigating the bewildering landscape of 21st-century Britain, where women show their calves without shame, and the British Empire has collapsed into something far less glorious than he remembered.

Watching Gore grapple with concepts like bike riding, dating apps, and seven cigarettes a day (down from his Victorian norm) provides some of the novel’s most entertaining moments. One of the book’s strengths is the humorous narrative by Kaliane Bradley—on a number of occasions, I had to put it down and laugh out loud—which makes it a breezy page-turner you can read in four or five days.

‘I was somewhat in awe of her, and I translated this into artificial aplomb, because I imagined her a woman impatient with another woman’s self-deprecation.’

— The Ministry of Time

Bradley, a British-Cambodian writer based in London, conceived the novel during the COVID-19 pandemic while watching AMC’s “The Terror,” where Gore appears as a minor character. Her research on him and the lost Franklin expedition is impressive, along with the development of his charming character. Gore was described by his commander as someone with great stability of character and the sweetest of tempers, qualities Bradley brings vividly to life on the page.

During their months-long acclimatisation stay together, a slow-burning romance develops in the midst of other manoeuvrings by shadowy figures at the Ministry. What starts as a quirky workplace comedy gradually reveals darker undercurrents—the Ministry isn’t just conducting anthropological research but appears to have more sinister motives involving timeline manipulation and climate catastrophe prevention. The novel blends historical fiction, time travel sci-fi, romance and spy thriller elements, and most of it holds up. This genre-bending approach earned the book a Hugo Award nomination, and the Goodreads Choice Award for Science Fiction, and it even made Barack Obama’s favourite books list for summer 2024.

However, many of the characters in the present timeline are opaque, including the protagonist herself, which makes it difficult to work out their motivations. As such, the wheels of the narrative start to fly off in the later chapters. There is a particular falling out between friends in the story that is not well elucidated, even though it is pivotal to the story arc. Some elements are introduced too late to be fully explored and are left inelegantly dangling.

In some parts, I imagine that in order not to give away the twists, the author obscures some details, but she does so too much, to the point of losing the readers. There are also many instances of one-dimensional thinking that stretch credibility, but most peeving is the lack of urgency in the protagonist’s actions. When bodies start dropping, and a number of them do, despite the good use of foreshadowing, inexplicably, nothing seems to happen. Nothing jars her awake or spurs some action from her. Events seem to mostly happen to her while she remains frustratingly passive and obtuse.

The time travel mechanics themselves become increasingly problematic. Without spoiling too much, the novel eventually reveals a bootstrap paradox that some readers found undermined the entire premise. If you’re the type who needs your science fiction to be internally consistent, the final act might leave you cold.

Readers and reviewers alike criticised the novel for trying to do too much (and only succeeding partially) and settled on a 3-3.5 star rating. I would’ve given it a four-star rating for humour, steamy romance, and ease of reading. Even with the wobbles, I still finished it. I have read other sci-fis that did not suffer the same problems as The Ministry of Time, but they were laborious to finish because the readability was so low. Other readers also criticised it for numerous overdone metaphors, but those didn’t bother me at all. In fact, I hardly noticed them.

If you’re looking for a fun, emotionally engaging read that doesn’t take its science fiction too seriously, this is your book. Fans of light time travel stories who can forgive some plot holes for the sake of compelling characters and witty banter will find much to love here. If you’re a hard science fiction purist who needs every temporal paradox explained, you might want to look elsewhere. The novel works best when viewed as what it truly is: a romance wrapped in science fiction, with some genuinely thoughtful commentary on imperialism, identity, and displacement.

However, if you’d rather watch it than read it, The Ministry of Time is being adapted for TV as a six-part series on the BBC, produced by A24.